Call loans and speculation

Call loans are loans payable on demand. From the point of view of any one bank, a call loan seems to be a desirable form of credit, for when the bank reserves are threatened, or there is a demand for money for other purposes, repayment may be asked. But when some banks call loans, the borrowers put additional strain on other banks. Moreover, the general calling of such loans often forces speculators to sell their holdings to secure funds with which to repay their loans, just as the making of call loans at low rates generally stimulates buying of speculative securities on a large scale. In this way, such surplus reserves as appeared in the New York money market were absorbed in call loans, which led, in turn, to strong bull movements, that is, to rising prices on the stock exchange. When the reserves were brought down to the legal minimum, or in practice a little below, the tightening of the call-loan market often led to the precipitate selling of shares and a drop in stock market values. Altogether it will be seen that our inelastic reserve system worked in such a way as to bring about an unholy alliance between lending and speculation. The effect of fluctuations in the money market was felt in magnified form in the speculative market, while in turn, the ups and downs of speculation reacted upon the state of the money market.

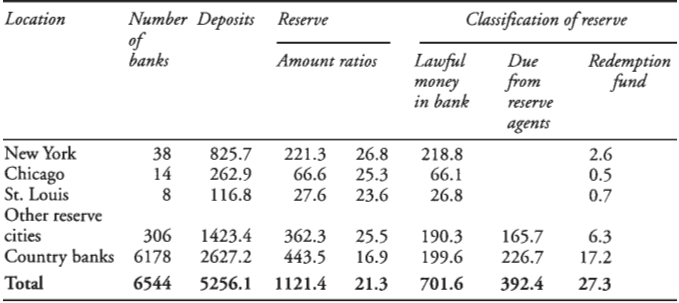

The dominance of the New York money market is shown, even though not fully, in the accompanying table, which, speaking for a period several years earlier than the introduction of the federal reserve system, shows the disposition of the cash deposits and the reserves of the national banks of the country. New York, it will be noted, held more than one-third of the reserves of the country, and in addition, it should be remembered that many state banks, private banks and trust companies had deposits in New York which they treated as their own reserves. The deposits of other banks generally constituted more than one-half of the deposits of New York banks. Like an inverted pyramid upon its apex, the whole structure of bank credit in the United States rested upon the cash reserves of the New York national banks.

Table 35.1 Deposits and reserves of national banks (sums in millions of dollars)

The importance of speculation in its relation to the money market is indicated in the accompanying table, which shows the character of the loans and discounts of New York national banks in 1890 and 1912. In interpreting the table, it should be noted that not only most of the loans made on call, but also some of the time loans made on collateral security, were for the purpose of financing speculative transactions.

The fundamental difficulty may be put in this way: there was nowhere any slack or “give” in our banking system. The whole system tended always to be in a condition of strain. Whatever slack might appear was at once taken up or absorbed in the speculative market. There was no possible remedy save in a more elastic relation between loans and reserves, and that was impossible without centralized control and centralized responsibility. Sometimes the best interests of the country demanded a banking policy which ran counter to the interests of individual banks. Such a policy in the nature of the case could not be the outcome of the operations of competitive banks, however public spirited.

Table 35.2 Loans and discounts of New York national banks: 1890 and 1924 (in millions of dollars)

| Character of loan | 1890 | 1924 |

| On call | 102 | 623 |

| On time, with collateral security | 43 | 475 |

| On time, without collateral security | 152 | 873 |